Radio Security Services

Bill Amos, Voluntary Interceptor, at work.

[Artist - Sheena Phillips]

As an important part of Wireless Intercept (the ‘Y’ Service, so named) the Radio Security Service (R.S.S.) began life in the unlikely surroundings of Her Majesty’s Prison, Wormwood Scrubs! It was managed by the Secret Intelligence Service and initially given the title of MI8(c). M.I.6 took over its management from May 1941 onwards. The initial purpose of the R.S.S. was quite specific, as it was established to uncover any active German agents operating from within the U.K. who, for example, might be providing broadcasts to aid aircraft navigation as well as passing on military secrets.

Among the plethora of radio signals emanating from Europe, radio ‘hams’, recruited by the R.S.S., soon uncovered a sub-level of signals, faint and distorted certainly, but understandable to the trained ear. Realising in addition that these signals were formed of unintelligible letters in groups of five, clearly some form of secret code, the R.S.S. knew it was on to something important.

The Radio Security Service believed that its operators were intercepting signals coming from the German intelligence service, the Abwehr, and from other Nazi security organisations. These filled the air waves from Germany or German occupied Europe on a daily basis. Military radio traffic was not its concern as this was covered by the varied military radio intercepting organisations in Y service.

Short wave radio signals are notoriously unstable and to be sure of interception a number of radio interception stations were built across Britain, each with large aerial arrays and several huts and ultimately employing upwards of 1,500 operators maintaining a twenty-four-hour watch.

In the early months of the war an immediate response was, however, fraught with practical difficulties since it would take time to build such structures on a nationwide basis. To provide the blanket coverage required as quickly as it could, the R.S.S. approached and enlisted the aid of a large number of skilled radio hams (amateur radio enthusiasts), called Voluntary Interceptors (V.Is). These were recruited from among the most skilled of Britain’s pre-war radio amateurs, often members of the Radio Society of Great Britain. Self-evidently members already had the necessary short-wave radio receivers needed to pick up transmissions and the skills to operate them, though they had had their transmitting crystals impounded at the outbreak of war.

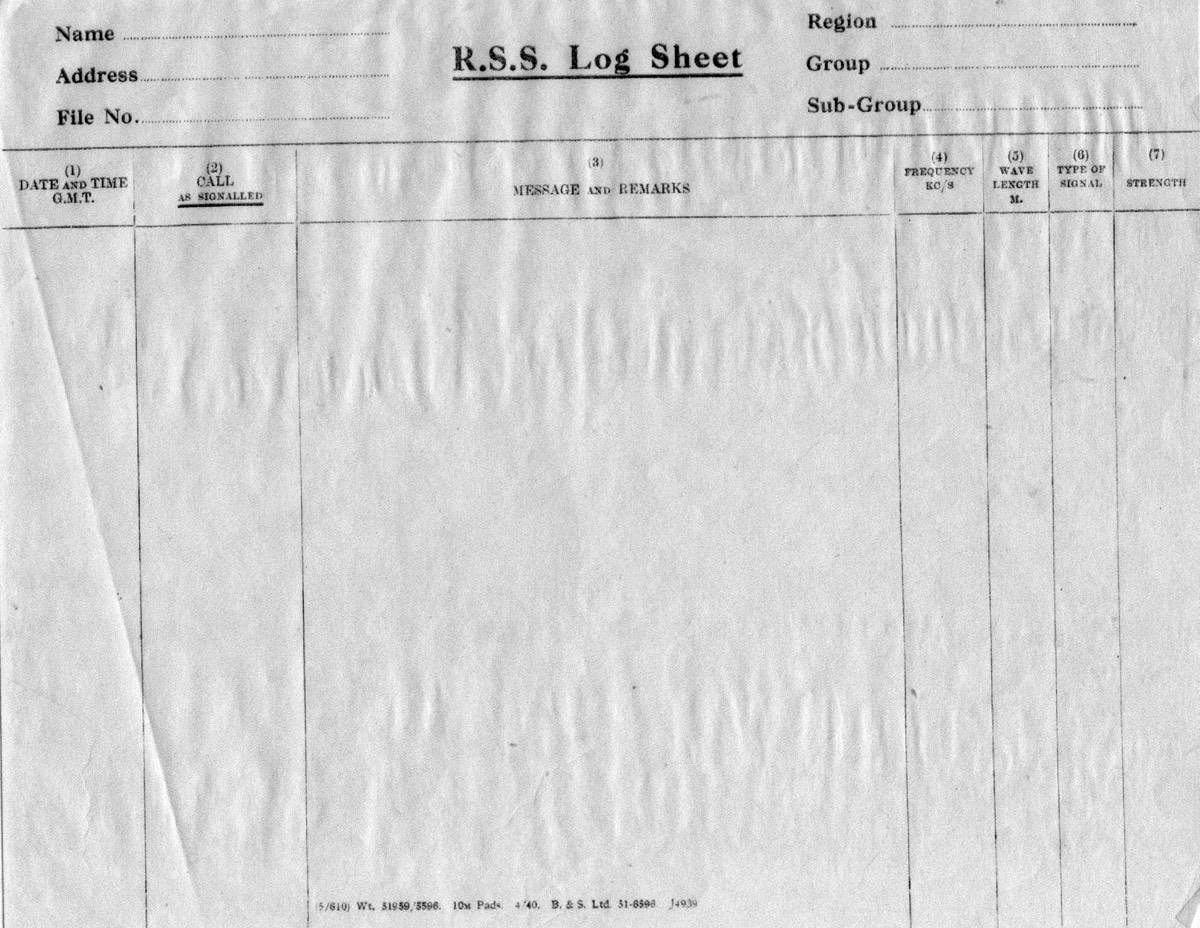

Since most of them would have had day-time civilian jobs, they carried out the bulk of their work at night and often operated from their own homes or businesses. They carried out the same function as the R.S.S. stations by monitoring radio frequencies for any unexpected transmissions and any intercepted messages thus discovered were noted upon an RSS signal pad, placed in an envelope inside another envelope and forwarded to P.O. Box 25, Barnet, the intercept station R.S.S had established at Arkley View in Barnet, London. In effect this became a staging post in a line which led ultimately to Bletchley Park, the location of the secret Government Code and Cipher School. There, a vast effort was being expended on the crucial task of breaking Germany’s Enigma code and upon the rapid deciphering of Enigma messages. At one point some 10,000 V.I. log sheets were being sent to Arkley View!

Among the plethora of radio signals emanating from Europe, radio ‘hams’, recruited by the R.S.S., soon uncovered a sub-level of signals, faint and distorted certainly, but understandable to the trained ear. Realising in addition that these signals were formed of unintelligible letters in groups of five, clearly some form of secret code, the R.S.S. knew it was on to something important.

The Radio Security Service believed that its operators were intercepting signals coming from the German intelligence service, the Abwehr, and from other Nazi security organisations. These filled the air waves from Germany or German occupied Europe on a daily basis. Military radio traffic was not its concern as this was covered by the varied military radio intercepting organisations in Y service.

Short wave radio signals are notoriously unstable and to be sure of interception a number of radio interception stations were built across Britain, each with large aerial arrays and several huts and ultimately employing upwards of 1,500 operators maintaining a twenty-four-hour watch.

Voluntary Interceptors

In the early months of the war an immediate response was, however, fraught with practical difficulties since it would take time to build such structures on a nationwide basis. To provide the blanket coverage required as quickly as it could, the R.S.S. approached and enlisted the aid of a large number of skilled radio hams (amateur radio enthusiasts), called Voluntary Interceptors (V.Is). These were recruited from among the most skilled of Britain’s pre-war radio amateurs, often members of the Radio Society of Great Britain. Self-evidently members already had the necessary short-wave radio receivers needed to pick up transmissions and the skills to operate them, though they had had their transmitting crystals impounded at the outbreak of war.

Since most of them would have had day-time civilian jobs, they carried out the bulk of their work at night and often operated from their own homes or businesses. They carried out the same function as the R.S.S. stations by monitoring radio frequencies for any unexpected transmissions and any intercepted messages thus discovered were noted upon an RSS signal pad, placed in an envelope inside another envelope and forwarded to P.O. Box 25, Barnet, the intercept station R.S.S had established at Arkley View in Barnet, London. In effect this became a staging post in a line which led ultimately to Bletchley Park, the location of the secret Government Code and Cipher School. There, a vast effort was being expended on the crucial task of breaking Germany’s Enigma code and upon the rapid deciphering of Enigma messages. At one point some 10,000 V.I. log sheets were being sent to Arkley View!

Example of the log sheet used by VIs.

Monitoring German Radio Traffic

By listening to an individual, designated and narrow range of frequencies, the V.Is became accustomed to the regular radio signals (e.g. commercial, military), would in time ignore these and would instead focus on the occasional, faint transmissions which were of much more interest to Barnet and Bletchley Park. This was not easy work and required intense and sustained concentration since Short Wave radio signals are severely and often adversely affected by changing conditions in the ionosphere. In addition, of course, the Germans made every effort to ‘hide’ their transmissions beside existing broadcasting stations, by shifting to a different wavelength and by leaving time gaps in the broadcasting. Being a V.I. was very tiring work, often carried out in the low-point hours of the night and requiring great maturity and persistence.

Having made an intercept, the V.I. noted details of the Morse Code message (usually in five letter groups), the call sign of the station, the time of transmission, the signal strength and so on. Obviously, the V.Is were clueless as to the meaning of such coded messages, messages which were often being produced by the Germans' Enigma encoding machines.

A late version Enigma Encoder with five rotors not the original three.

To forestall damaging gossip and to provide additional anonymity, V.Is were enrolled in the Royal Observer Corps. Despite such measures, the secrecy surrounding the R.S.S. was surprisingly breached when an article on the work of the organisation appeared in the Daily Mirror on 14 February 1941. This article noted that:

"Britain's radio spies are at work every night...Home from work, a quick meal, and the hush-hush men unlock the door of a room usually at the top of the house. There, until the small hours, they sit, head-phones on ears, taking down the Morse Code messages which fill the air."

VIs often found it difficult to explain why they were unable to play a part in, for example, Fire watching or Home Guard duties. They simply didn’t have the time and were unable to explain, being bound to silence by the Official Secrets Act.

"Britain's radio spies are at work every night...Home from work, a quick meal, and the hush-hush men unlock the door of a room usually at the top of the house. There, until the small hours, they sit, head-phones on ears, taking down the Morse Code messages which fill the air."

VIs often found it difficult to explain why they were unable to play a part in, for example, Fire watching or Home Guard duties. They simply didn’t have the time and were unable to explain, being bound to silence by the Official Secrets Act.

Haddington’s

Bill Amos

North Berwick’s

Mr Coventry

V.Is - Mr. W. Amos And Mr. Coventry

No one really knows exactly how many V.Is there were. The total was somewhere between 1,500 and 1,700 but no record appears to have been kept listing who they were. However, it is known that at least two East Lothian men were V.Is and members of the Radio Security Service. Mr. Amos of Haddington and Mr. Coventry of North Berwick both carried out radio monitoring work for R.S.S. Nearby in the Borders area other radio amateurs became V.Is, including Stan Brigham G2FXB, Chief Station Clerk at Berwick railway station, and John Blair GM5FT who ran a radio and bicycle shop in Selkirk’s main square.

Bill Amos

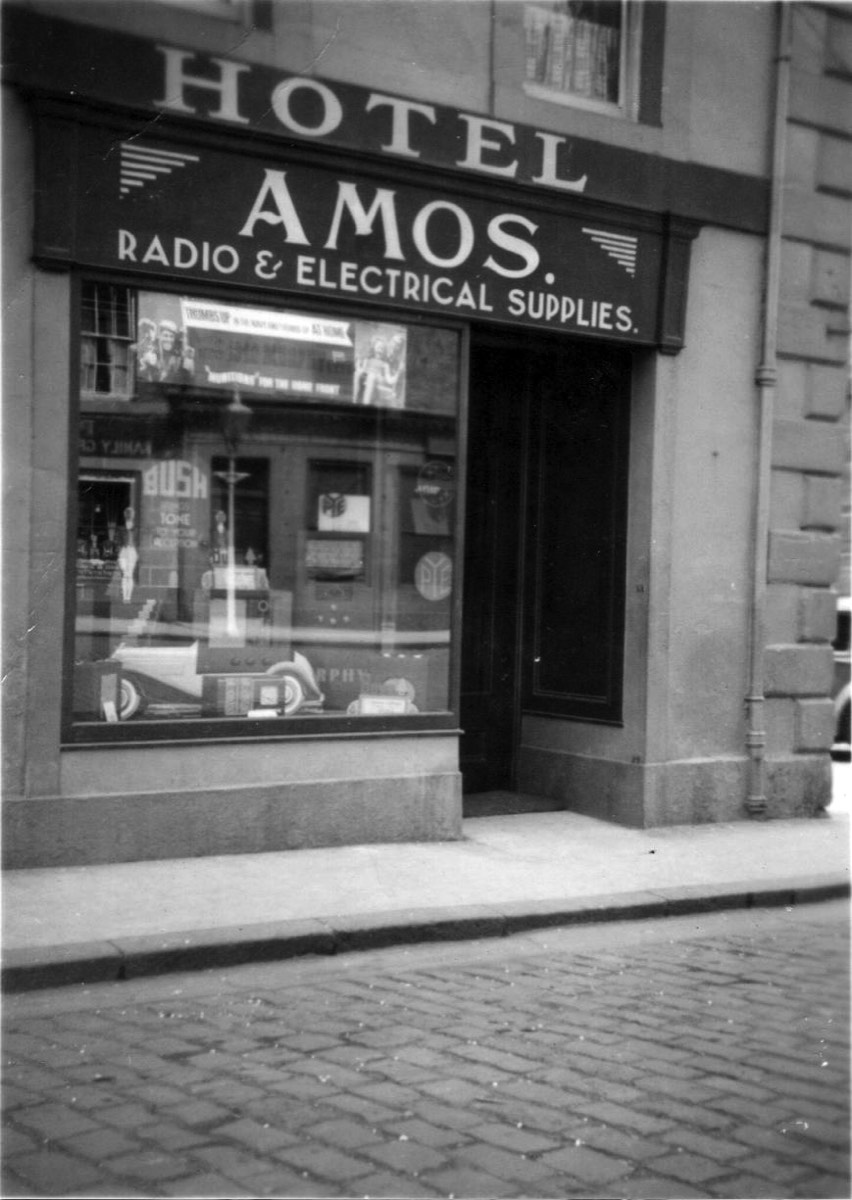

Bill Amos’ shop in Market Street, Haddington: now and then.

At the time Bill Amos ran a radio shop in Haddington’s Market Street (now Gibson’s). From his shop Mr. Amos sold radio and electrical parts and supplied radio owners with the accumulators or batteries needed to work the radios in those parts of East Lothian as yet unconnected to the electricity mains.

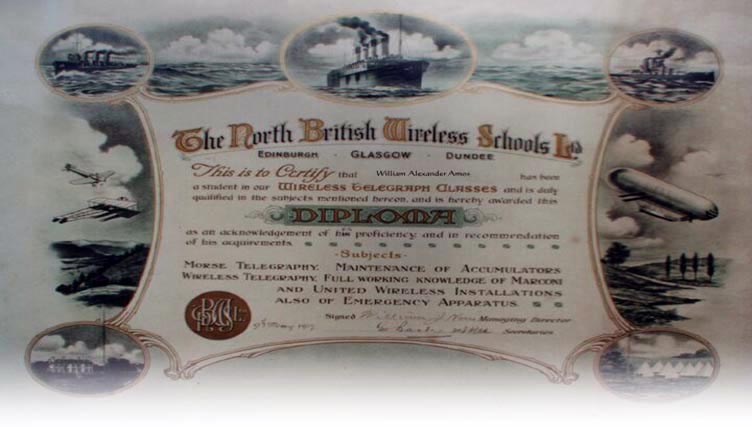

Bill had trained as a radio operator in the Mercantile Marine during the First World War and was especially skilful in making sense of faint radio signals buried and distorted by atmospheric static. While on a distant voyage he was the first Merchant Marine Radio Officer in the area to hear the faint signal announcing the end of the First World War and was able to inform his nearby colleagues in the Royal Navy of the fact!

Bill had trained as a radio operator in the Mercantile Marine during the First World War and was especially skilful in making sense of faint radio signals buried and distorted by atmospheric static. While on a distant voyage he was the first Merchant Marine Radio Officer in the area to hear the faint signal announcing the end of the First World War and was able to inform his nearby colleagues in the Royal Navy of the fact!

Bill Amos’s Diploma in Wireless Telegraphy, 1909.

Mr. Amos’s recruitment had taken place early in 1940 when three men called at his home in Templedean Crescent, Haddington. On answering the door Mrs. Amos was shocked to discover three men on the doorstep headed by a policeman. She feared the worst! The Edinburgh based senior policeman asked to speak to Mr. Amos privately and Bill took the men out into the garden so as not to be overheard.

The group included an officer from the Security Service (M.I.5) and Captain Wallace MC, controller of a group of Voluntary Interceptors in the south of Scotland. In the dark and stillness of the garden they fully explained to Bill that they needed him for his skills as an experienced radio operator and that he was to work for the Radio Security Service on the interception of enemy radio broadcasts.

This was to be his introduction to the Radio Security Service, a somewhat hurried and clandestine ‘interview’ approach used on many other prospective V.Is.

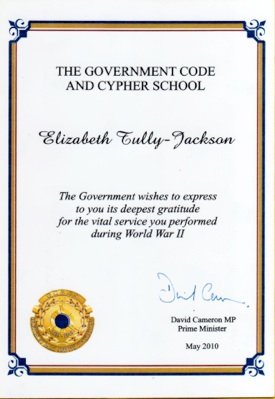

After his recruitment to the Radio Security Service Bill carried on with his shop as a cover for his work. He relied upon his assistant, Lizzie Young, to steer customers elsewhere when he was at work on radio interception. Lizzie had to sign the Official Secret’s Act which effectively silenced her and made it difficult for her to rebut the accusation by some in the town that she wasn’t doing her bit for the war effort. In 2010 Lizzie was posthumously awarded a medal and certificate recognising her contribution to the war effort.

The group included an officer from the Security Service (M.I.5) and Captain Wallace MC, controller of a group of Voluntary Interceptors in the south of Scotland. In the dark and stillness of the garden they fully explained to Bill that they needed him for his skills as an experienced radio operator and that he was to work for the Radio Security Service on the interception of enemy radio broadcasts.

This was to be his introduction to the Radio Security Service, a somewhat hurried and clandestine ‘interview’ approach used on many other prospective V.Is.

After his recruitment to the Radio Security Service Bill carried on with his shop as a cover for his work. He relied upon his assistant, Lizzie Young, to steer customers elsewhere when he was at work on radio interception. Lizzie had to sign the Official Secret’s Act which effectively silenced her and made it difficult for her to rebut the accusation by some in the town that she wasn’t doing her bit for the war effort. In 2010 Lizzie was posthumously awarded a medal and certificate recognising her contribution to the war effort.

Lizzie Tully Jackson (Young).

Lizzie’s certificate, awarded in 2010.

Bill set his radio receiver up in a small side building beside his shop. Effectively it was where he stored his accumulators and spares. At first he used his own receiver but later, like all other V.Is, he was provided with the latest types of Allied radio receivers.

An example of the advanced type of radio receiver employed by V.Is.

Lizzie recalled how many customers came into the shop looking for Bill and who had to be fobbed off with a range of excuses as he was busy upstairs doing his secret work. Lizzie had to become quite proficient in telling white lies and keeping a straight face!

Royal Signals Unit, West Garleton House

Technical and communication support for East Lothian’s V.Is (and for 201 Home Guard unit - see Auxiliary Units) was provided from West Garleton House, the Head Quarters of a small detachment of Royal Signallers. Sergeant Jack Milligan (later a Captain in charge of Intelligence School No.6 in England) and pictured here with a colleague on the steps of their billet in 18 Baird Terrace, Haddington, was one of the detachment who looked after Bill’s technical ‘health’ and his communications with higher authority.

Unusually, though not uniquely for a V.I., Mr. Amos received the British Empire Medal in January 1946 in recognition of his services. These must have been unusually useful to the R.S.S. and Bletchley Park. However, the entry in The London Gazette noted that the award was to "William Alexander Amos, Observer, Royal Observer Corps," highlighting the fact that the real reason he received his award could not be broadcast even then and mention could only be made of the cover organisation to which Voluntary Interceptors were attached.

Sergeant Jack Milligan (Left).

Mr. Coventry

Much less is presently known about Mr. Coventry and his work in R.S.S. He owned a fish shop in North Berwick and was, at one time, a Town Councillor. He lived on St Baldred’s Road and may have learnt his radio skills in the same manner as Mr. Amos, in the Merchant Marine in World War One. Perhaps you know something which would fill in this gap in our knowledge?

Identifying German Spies

As mentioned, the initial task of the V.Is was to detect transmissions from German spies operating in Britain and to help locate their position. They were given the authority to enter property from which they suspected illegal radio signals were being transmitted. It is now known that all German spies in Britain during the war were captured and either executed or 'turned' to become double agents, sending false information back to the Germans. This only became certain after the war, but during it the V.Is were able to make an informed guess that no German spies were at work simply from the lack of covert transmissions originating from within Britain itself.

A Spy In The Lammermuirs?

This, of course, didn’t prevent rumours circulating or indeed some of the wilder speculations of ‘Spy Mania’. At least one example of Spy Mania originated in East Lothian. According to the story a radio engineer living in East Lothian was woken in the night and taken by Military Police into the Lammermuir Hills where a number of soldiers had a civilian under arrest. The engineer was ordered by an Army officer to inspect a radio transmitter. When asked if it was capable of transmitting to Germany, the engineer answered yes. The soldiers then took the civilian away and there was a volley of shots in the darkness. The soldiers returned, and left again with shovels, a sound of digging being audible. The officer then instructed the engineer to forget what happened that night and never to talk about it, and he was taken back to his home. Rumour or fact? You decide.

Radio Direction Finding

V.Is were also employed in R.D.F. stations established to help locate the geographical position of broadcasting sets. Eight of these were established all over the UK and German broadcasting stations could be located whenever two or more of these stations were able to pinpoint their origin. Lines were drawn on a map from R.D.F station to source and when the lines from two or three R.D.F. stations crossed; the transmitting location was revealed.

Ultra

Mr. Amos and Mr. Coventry were merely two of over 1,500 Voluntary Interceptors. Nonetheless, their work was undoubtedly very important and was the bread and butter upon which the code breaking work at Bletchley Park depended. The information from Bletchley Park, code named ‘Ultra’, was reputed to have shortened the war by up to two years since it provided the Allies with highly secret German strategic and tactical information. This was clearly an immense advantage, for example, both in the Battle of the Atlantic and prior to D-Day and during its subsequent operations.